Last week I wrote about all the media furor over Miley's fucked-up cheerleader/porn-star drag at the MTV Music Awards, satirizing and taking seriously Miley's attempts at Madonna-ness: "[Dancing around like a stupid slut at a trailer-park prom] is her art. She has become the neo-neo-neo-Madonna. Madge almost thirty years prior did a rolling-around-on-the-floor-in-a-wedding-dress stunt on the VMAs that got her in 'hot water' too. And remember her glossy, awful

Sex Book? Remember her flaunting her "transgressive sexual power"? Remember Camille Paglia?"

Well somebody sure did remember Camille Paglia. She was enlisted to sum up the whole tragic Miley debacle in

Time Magazine. Camille even got her name on the cover. Damn.

And the essay she wrote has a mummified unintentional self-parody to it that seems stolen from an outtake of

Waiting for Guffman. Camille chastises Miley for being "disgusting" and "artless" and "crass," while canonizing Madonna for all her artfully executed hijinks, the Original Genius Bad Girl. The peak moment in Camille's essay in

Time comes right smack dab in the middle, when she kisses Madonna's ass so magnificently you just cannot believe your eyes: "Young performers will probably never equal or surpass the genuine shocks delivered by the young Madonna, as when she sensually rolled around in a lacy wedding dress and thumped her chest with the mic while singing 'Like a Virgin' at the first MTV awards show in 1984. Her influence was massive and profound, on a global scale. But more important, Madonna, a trained modern dancer, was originally inspired by work of tremendous quality — above all, Marlene Dietrich’s glamorous movie roles as a bisexual blond dominatrix and Bob Fosse’s stunningly forceful strip-club choreography for the 1972 film

Cabaret, set in decadent Weimar-era Berlin. Today’s aspiring singers, teethed on frenetically edited small-screen videos, rarely have direct contact with those superb precursors and are simply aping feeble imitations of Madonna at 10th remove."

I remember that "Like a Virgin" stunt, and it wasn't in any way "sensual" or "profound" or an example of "trained modern dance." And Marlene Dietrich or Bob Fosse were nowhere in the schtick. It was just the slutty, stupid, young Madonna rolling around on the floor with a microphone stuck up to her mouth, singing "Like a Virgin" as if she were drunk and throwing a sleepy tantrum. Her singing voice was pretty sad, just like Miley's, as both young ladies were focused primarily on trying way too hard to push buttons the way young and slutty people often do. Which makes both preeminent moments in pop culture, Madonna rolling around on the floor, and Miley rolling her tongue outside her mouth, hilarious. Just plain god-awful funny.

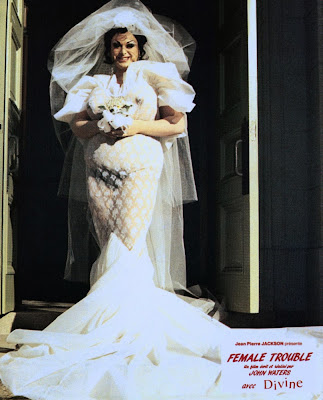

Which brings me to Divine, the goddess both of these gals seem to be referencing, intentionally or not. Divine, who passed away in 1988 of heart failure, was the star of many John Waters' films, but the one I love him in the most is

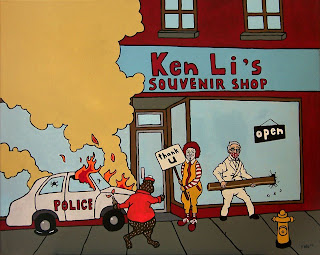

Female Trouble. In this highly stylized and completely enjoyable romp from 1974, Divine plays Dawn Davenport, a morbidly obese teen-aged runaway who grows up to be a white-trash superstar addicted to both drugs and fame. (Ring any bells?) In the movie, Divine sports many uniquely fabulous looks, including the two in the photos above: a see-through wedding gown and a strappy sequined pantsuit number. Both these looks would definitely be at home on the MTV Video Music Awards stage, whether worn by Miley, Madonna, or Gaga. But more importantly, it is the way Divine acts that brings to mind what is missing in both Madonna's and Miley's oeuvre. There's a bit of angry tragedy in Divine's portrayal of Dawn, a maniacal need at the core of her performance. Divine plays Dawn with an un-ironic gusto that supersedes vanity, and therefore a true picture of something depraved and ravenous and hilarious is revealed. She makes the horror of Dawn's spectacle turn into a sort of wild beauty.

Miley didn't. Madonna didn't either. Camille wants to critique Miley on the grounds of "high art," but really it's a different kind of art and territory on which Madonna and Miley and other pop provocateurs should be judged: drag. And Divine set the standard. He provoked and performed with a sense of abandon and yet with no need to please his audience. He seemed completely intent on finding a way out of popularity and into a sort of grandeur beyond "art" or even "fame." He mocked "art" and "fame" with his smart-assed yet authentic display of desire. Divine was punk, outsider-art, pop-art, low-art, high-art, and decadent Weimar-Republic, all rolled up into one horribly beautiful package in

Female Trouble.

He is actually what Camille calls the "superb precursor." Madonna was simply aping feeble imitations of Divine at 10th remove.

To read the Camille's full and hilariously fusty essay about Miley:

Camille on Miley in Time Magazine.