I Am Divine is a new documentary about probably one of my favorite artists who ever walked the face of the Earth: Divine. This picture does him justice: glamorously monstrous, beautifully horrible, and yet a kind of defensive innocence glitters from his eyes. Mockery and sympathy contend with each other in the way he presents himself. I refer to him as "him" because I think that is what he always wanted: the masquerade did not change who he actually was; it was only a device to show how fucked-up and beautiful everything is.

Divine, or Glenn Milstead, is one of those penultimate figures in my life. He was punk, queer, down-home, sloppy, stupid, sarcastic, bombastic, crazy, lovely, and so on. I first saw him via VHS, 1985, when I was an art-school dropout in Indiana, washing dishes for a living, dropping acid, smoking Salem Lights and eating Little Debbie's Oatmeal Cream-pies for breakfast, lunch and dinner. It was Pink Flamingos, and what a terrible and glorious introduction. Simply iconic, Divine wore clownishly femi-nazi make-up (created by the genius Van Smith), tight-fitting ball-gowns, and brandished a pistol in the cold air outside her junkyard trailer. She had a posse of tragicomic misfits that somehow seemed completely pleased with themselves, arrogantly mean-spirited, selfishly unaware of their own joke and yet completely committed to it. Divine in the movie is total woman, dolled up and pissed off, ready to eat dog-shit at any moment, incredibly proud of her own demonic nature, and yet also chatty and sweet with those of her own kind. In short, she was a lot like the white-trash folks I had grown up with, only glazed with freak-love, popping out of the ordinary nastiness because Glenn Milstead (and John Waters of course) had willed this beautiful monster into being to lead the way toward the Abyss. Waters gave Divine a universe to be pissy and mouthy and elegant in, a brown ugly landscape of muddy hills and brambles and broken-down cars, and Divine graced that pit with an angry otherworldliness. She was a goddess creating her own origin myth while shoplifting chuck-roast in between her legs.

In I Am Divine, John talks about the day he and Glenn first saw each other, in high school. They were both seventeen. John's dad was dropping him off at school, and they both spotted Glenn waiting to go into school. Glenn was dressed in preppy anonymous clothes, John says, and he was definitely trying to camouflage himself in normalcy, but obviously could not hide what John calls his "nelly-ness." John's dad quietly noticed Glenn too, according to John: his dad's face got stony, angry, right at the moment he spotted Glenn.

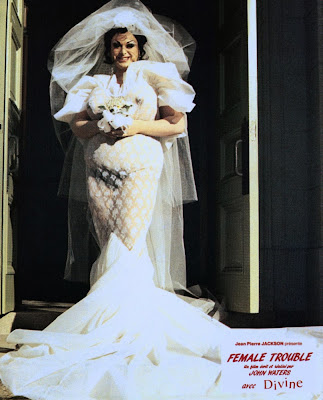

Glenn could not hide his "Divine." Even if he tried really really hard. And so he eventually understood instead of hiding he would need to scream and flail and display his "nelly-ness" to the point people were afraid of it, afraid of his power. And God did he have power. In Pink Flamingos, in Female Trouble, in Polyester, and even in Hairspray, Divine was something never seen before or since: all fury, all horror, and yet completely real, down-to-earth, hilarious, intelligent. He didn't create a character (John did that); he created an atmosphere of self.

At the end of the documentary, Glenn's agent talks about seeing Glenn dead in his motel room in 1988. (Glenn died of a massive heart attack in his sleep.) That day he died was going to be one of those penultimate moments for Glenn: he was going to start a stint on Married with Children, not as Divine, but as another character the writers had created for him. And that character was a man, which made Glenn very happy. The agent narrates what she saw that morning: the Married with Children script carefully placed on his nightstand, his bed-slippers next to the bed, the suit he was going to wear laid out on a chair.

And Glenn in bed, gone from this world.

"He was beautiful," the agent said.

The poignancy about that whole scene is his preparedness, his optimism, his work ethic. He was dedicated to finding ways of turning people's heads inside out.

That takes a lot out of you.